the conqueror

There was nothing I could do to make him look like Genghis Khan.

The first problem was the eyes. He does have narrow eyes, slits, made for scanning a distant horizon, blocking out the glare of the sun and keeping the trail dust out of the tear ducts. But he wanted me to make them look “more Chinese.”

I found that nothing I did seemed to satisfy him.

We filmed in Technicolour. Thankfully he decided not to paint his face. I had to do that on The Twelve Coins of Confucius. The makeup smears and you go through it like nobody’s business. I feel that it disguises the natural lines of the face and makes the performances more wooden. You lose the subtle creases at the corners of the mouth that give an expression its depth, allow you to convey something more complex than a smile or a frown.

I don’t think there’s any reason that a warlord of the Mongols shouldn’t have access to the same spectrum of emotion as any other man. In some ways I thought that was the whole point of the picture.

But the dust was a problem. We filmed in Utah, out there in the desert where he does everything. I think with paint it would have proved unmanageable.

The air dried everything out. The hot wind blowing over the set, half-burying the canvas yurts and the wooden palisades of our Peking. We had to dig them out each morning. The luxuriant moustaches of our mandarins dried and shrivelled. It was my responsibility to oil them.

We wound up shaving half the extras bald. Letting them be eunuchs. The Paiutes didn’t like it but it was in their contract.

When the wind blew from the west the horses became nervous.

I guess we found out later why that was. Animals can smell things people can’t. They have a whole extra layer of senses. The handlers couldn’t understand it. We had a whole crew of stunt-riders, Mexicans and Apaches from down south, to handle the war scenes. They were experts at falling off their horses. I’ve never seen anything like it.

It wasn’t a bad production, all things considered.

Some of the riders had been working with him for years. Way back in the war days. They’d forded raging rivers while he plinked away from them from some secluded bolthole in a hillside and chased his stagecoach across salt flats, firing arrows calculated to miss. They said he wasn’t a bad person once you got to know him.

Just remote. They said he regretted not fighting in Germany. That he bought drinks for the extras and made sure the whole crew knew it. That he believed queers controlled the industry and he was the only regular working joe left. You couldn’t get a part now if you weren’t a queer. He thought of himself as a legacy admission.

I couldn’t get his hair right. He wanted something done with his eyebrows but he wasn’t sure what. He knew he needed a moustache but he’d never had one before and he couldn’t decide how thick he wanted it to be. It was hard to convince him that he wasn’t allowed to change it between scenes.

He didn’t change his voice. I sympathise. The convention seems to be that you use an English accent, a sort of BBC announcer voice that conveys an appropriate sense of the grandeur of history. But it hardly seems to work for Genghis Khan. The press made fun but it’s hard to see what else he could have done.

But he had no sense of humour about the production. He didn’t see that there was anything even unintentionally funny about a Mongol king who talked like a county sheriff. He couldn’t comprehend that anyone, anywhere would make fun of him. He never felt he got the respect he deserved.

The original script was wildly ambitious.

What happens sometimes is they read a book on a new subject and become completely fixated. A whole cinematic universe unfolds before their minds. They start thinking of all the possibilities. I’ve seen it happen with Dodge City and Napoleon. I don’t think we recognise how many of our beloved film traditions are the product of one lonely producer’s accidental obsession, his imprinting on some second-hand paperback.

The people who get it the worst are the ones who aren’t big readers to begin with. They open a book for the first time in five years and it’s like they hadn’t realised what was possible.

The Mongols got everywhere. He liked to talk about it. He kept telling us they’d fought in Egypt, in Hungary. He wanted to see them invade Japan, intervene in the Crusades. A five-hundred-year epic. I think it was rare that he found someone else he could respect.

Of course we had to cut it down.

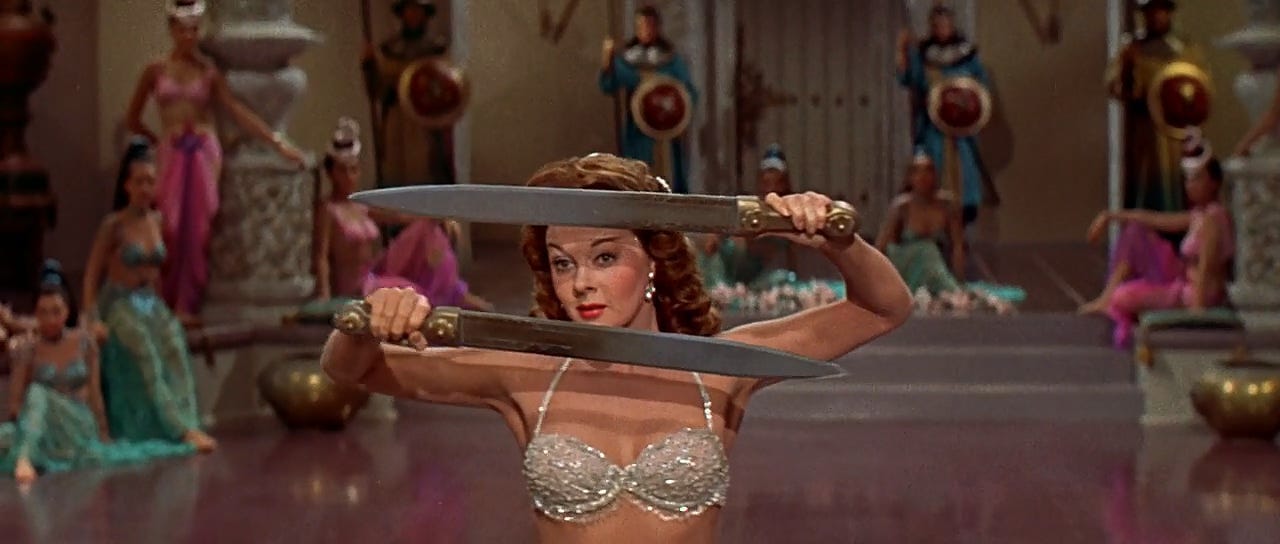

He fought to keep the sword dance of the Tartar princess. I don’t think they were sleeping together. I remember the costume, a sort of cascading veil thing with a painfully high conical hat. I had to pin it to her hair. If you replay the scene where she enters his tent you can see her duck just slightly to stop it falling off.

I worked hard on her eyes. She wanted them wide, not Chinese at all. She wasn’t interested in accuracy. She had a way of moving only her body. Keeping her head still, meeting his imperious gaze. Serpentining her hips. Very tame but undeniably sexy. I think in a different film it could have been very effective.

I saw her last year before she went.

She said she didn’t regret it. She’d always wanted to work with him. She couldn’t possibly have known.

I don’t think that’s true.

I’ve gotten in touch with as many of the extras as I could find. The Paiutes were hardest to track down at first. Most of them went back to their villages. Little places. Not on any map. I found one guy working as a street sweeper in Chicago, of all things.

Being an extra’s not a career. Every so often you meet a guy who thinks he’s going to get recognised, wants to give you a manila folder full of headshots. But very few of them are that stupid. They know it’s more like a hobby than a proper job.

We bus them out into the desert. Put them up for a few months. The catering’s always very good. We like to use locals when we can, save on accommodation, but often it’s easier just to move people around.

A couple of the stunt riders were still trying to work, right up until the end.

I think he could have known. The location scouts could have picked it up. What I don’t understand is why he filmed there at all. He was a man of habit. He had his spots, his monuments, that he liked to come back to again and again. We’ve all seen them. Quiet country towns in uninhabitable landscapes.

He’s lying to you in every shot. You must know that. The settlers lived in grassy plains. Not deserts. No matter how dramatic the rocks are. I think you can sense that in the films. The family farm he saves from some greedy cattle baron, some marauding tribe, has no grass in its fields and no access to water. The sunset’s beautiful but there’s no way any real person ever called it home.

I wonder if he got sick of it. His own myth. If he was looking for a new myth to replace it. A new corner of the earth to make legendary.

I don’t know if he knew what had happened there.

But I think he was superstitious. He liked the association with power. The workshop of a colossus, holding the world in its grip. The gun at the head of the world, compelling it to act justly. The Mexican standoff of nations with the white hat sure to win.

And he was a linear thinker. I don’t think he believed in unintended consequences.

The curious thing is that if you watch his later films, his middle-aged work, some of the sadness comes out. He’s playing a bully, a condescending uncle, a practical joker who uses his undeniable competence to humiliate the less fit. Yet nobody seems to notice. A man who is just barely managing, by dint of enormous effort, to impose his fantasies on the world.

He made a comedy once. It was about a landlord spanking his bitchy ex-wife. He wrote it himself. It was a huge success.

But I don’t think he was stupid.

I haven’t spoken to him since. There’s no-one we could possibly seek justice from. It’s possible that we could blame him, and some of the crew do. They think he robbed them. They hold him responsible for the hole in their lives, the indignity and inconvenience of their retirement. Even the ones who’ll make it have no money.

But I don’t know what we could take from him. Everything he still has can’t be taken.

I won’t be one of the lucky ones. My doctor is not the best money can buy but I don’t think in my case he has a particularly difficult job. We knew early on how it would go.

I never smoked. I wish I had. It gives you wrinkles but now I don’t have to worry. My husband is angrier than I am.

I think it was the wind.

Months on set, out in the open every day. Never far from the testing site. The wind howling every day, bombarding us, drying out our skin. Carrying the dust.

I was at the premiere. I didn’t want to go but he insisted. I’d been with him every day, tinkering with his costume, fixing his hair. Trying to make him the King of the Mongols. I think he felt bad. He knew he’d given me a pointless task.

I remember sitting there, in the cool dark room, watching the silhouette of his head in the front row. Only a few seats away. Watching himself on screen, twenty feet tall. Striding across the desert in a fur cape, cutlass at his belt.

I remember the silence. Polite, at first.

Then he opened his mouth. And, maybe for the first time, he heard himself.